KAʻILEADING WORDS

Kaʻi - Leading Words And Types Of Hawaiian Nouns

Nouns in English are preceded with a part of speech called a "determiner". These are words like "a", "the", "this", "that", "some", "his", "her", and so forth. These leading words, in the Hawaiian language, are called "kaʻi". Additionally, there are kaʻi which perform other grammatical functions such as pluralizing a noun. With only a few exceptions, all Hawaiian nouns must be preceded by a kaʻi.

Hawaiian nouns are divided into a number of categories which, in some grammatical forms, determine where the noun will occur in the sentence structure. As a beginning learner of the language it's not necessary to memorize the different terms. As an intermediate or advanced learner, the terminology becomes increasingly important. The basic categories of Hawaiian words related to nouns are:

- Memeʻa: A general term for either a common noun or a verb. Common nouns are places, things, ideas, or types of people ideas that are generic. Examples include "beach", "toy", "love", and "farmer". Since this broad category also includes all the types of verbs it essentially encompasses everything except Ioʻa (Proper Nouns). In Hawaiian, verbs (with some adjustments and constraints) can be used as nouns and, hence, memeʻa is a category that effectively means "a word" (but not a Proper Noun)

- Ioʻa: In Englishe, these are called "Proper Nouns". They are the words used as a name of a person, place, or organization and they are always capitalized. Examples are: "Mary", "Iokepa Bardwell", "Kahului", "Red Cross"

- Kikino: This subset of Memeʻa are those nouns that are entities with a body or shape of some type. They aren't places or ideas. In practice, most nouns are kikino. Examples are: "cat", "mango", "cloud", "wife", "child", "farmer", "toy"

Ka / Ke - "The"

The kaʻi "ka" and "ke" precede nouns (kikino) and mean exactly the same thing - "the". They are the most common kaʻi that youʻll see. Examples: Ka ʻīlio (the dog), Ke keiki (the child).

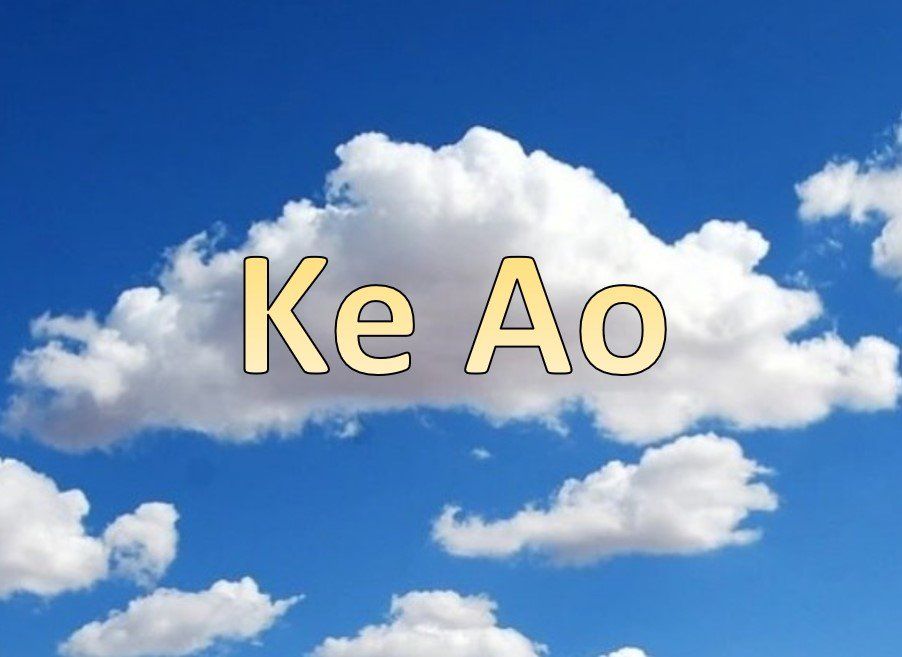

Some nouns take "ka" and others take "ke". There is no arbitrary reason why this distinction is made. To the right you see a picture of a cloud, "Ke Ao" (the cloud). This word serves as a memory aid for which nouns take "ke". If a noun starts with the letter "K", "E", "A", or "O" it takes the kaʻi "ke", otherwise it takes "ka". Remember that the ʻokina is considered a letter of the Hawaiian alphabet and, thus, words that start with an ʻokina take "ka", for example: ka ʻīlio (dog), ka ʻāina (land), ka ʻōlelo (language, speech).

There are exceptions to this "rule". In a very few cases a word has a different meaning with "ke" versus "ka". A complete list can be found in the Hawaiian Reference Grammar document (search the document for "taking ke instead of ka"). The most significant exceptions (ones that youʻll encounter in day-to-day conversations) include:

Ke pākaukau - table

Ke pā - Plate, dish

Ka pā - yard, field, pasture, fence

Ke penekala - pencil

Ke poʻo - head of a person or animal

Ka poʻo - head of an organization, director summit

Ke puna - spoon

Kēia, Kēlā, Kēna - "This", "That"

These three kaʻi mean "this" and "that"

Kēia - "this" as in ʻIke au kēia pōpoki (I see this cat)

Kēlā and Kēna both mean "that" but they imply two different locations for the thing to which they refer.

Kēlā - "that" as in ʻIke au kēlā pōpoki (I see that cat). In this case, the cat is "over there" or "far away". You, the person I'm talking to, can't reach out and pet the cat. Kēiā implies that the "that" is not within the reach of the listener.

Kēna - "that" as in ʻIke au kēna pōpoki (I see that cat). In English, this sentence is exactly the same as the previous one. In Hawaiian, kēna implies that the "that" IS within reach of the listener. The cat is right there, probably rubbing up against the listener's leg, and you're saying "I see that cat". You're assigning a location reference, indicating that the thing to which you're referring is near the listener. "Near" is, essentially, within arm's reach (but that's not an arbitrary distance rule).

He And Kekahi - "A" / "An"

While ka/ke imply the concept of "the" (ka ʻīlio - "the dog", he and kekahi imply, simply, "a" (he ʻīlio, kekahi ʻīlio - "a dog". Both he and kekahi are kaʻi and fullfull the requirement that Hawaiian nouns must be preceded by a kaʻi.

"He" only appears as part of a class-inclusional sentence (also called an "Is a/Have a/Has a" sentence), for example: He ʻīlio kēla - "That is a dog" or He ʻīlio kaʻu - "I have a dog". Refer to the He Class-Inclusional Sentence section for more details.

Pluralizing With Nā and Mau

To make a noun plural in English we typically add "s" or "es" ("dog" becomes "dogs", "bus" becomes "buses"). In Hawaiian, the kaʻi "nā" replaces either ke or ka in front of the noun, making it plural. For example: ka ʻīlio (the dog), nā iīlio (the dogs). Note that there are some nouns, referred to as "mass nouns" that donʻt change when theyʻre pluralized. For example, "fish" as in "I saw a fish" and "There were lots of fish in the ocean" (Not "fishes").

There are some grammatical situations where the nā pluralizer doesn't work. For example, in the He Class-Inclusional Sentence Structure the leading "He" (meaning "a") is the kaʻi. For example: He ʻīlio kēla - "That is a dog". Since the kaʻi role is filled by the He you can't add a second kaʻi, "nā", to pluralize "dog" into "dogs". In this situation you use "mau" to make the noun plural: He mau ʻīlio kēla - "Those are dogs".

Donʻt confuse the pluralizing "mau" with the stative verb "mau". The two words are spelled the same but have completely different meanings. The verb, "mau" means "always", "unceasing", "preserved" as in the Hawaii state motto, first spoken by King Kamehameha III on July 31, 1843, the day that sovereignty was restored to the Kingdom of Hawaii by proclamation of Queen Victoria following a five-month-long rogue British occupation: Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono. This phrase breaks down as follows:

Ua - past-tense marker

Mau - perpetuated, preserved

Ke Ea - the sovereignty

o ka ʻĀina - of the land

i ka Pono - due to righteousness

"The sovereignty of the land is perpetuated in righteousness"

Additional Pluralizing Kaʻi

In addition to the most commonly seen pluralizing kaʻi "na" and "mau" there are three additional pluralizers to recognize:

poʻe - used for people: ka poʻe wāhine - the women

puʻu - used for lifeless things: he puʻu pohaku - a pile of stones

pae - used for lands or islands: kēia pae moku - these islands

Notice that these pluraliziers change the conceptualization of the noun from being a single object to being a group of the objects. The group, itself, is now acting as a new "thing" and, hence, it is preceded by a kaʻi (ka, he, kēia, etc.). In effect, these pluralizers convert the stand-alone noun into a "collective noun" (see the next section for details).

Nouns The Convey An Implied Plural Sense: "Collective Nouns"

There are a number of Hawaiian nouns which, by the nature of the object itself, imply plurality. These nouns are called "collective nouns" or "mass nouns" and they don't use "na" or "mau" to make them plural, they are already plural in concept. Here are some examples:

| Ka wai | The water | Ka ono | The sand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ka ʻohana | The family | Ka papa | The class | |

| Ka pūʻā | The herd | ka iʻa ku | The school (of fish) | |

| Ka hui | The group | Ka kaulua | The pair | |

| Ka panalāʻau | The colony | ka ʻau moku | The fleet | |

| Ka poʻe | The people | Ka ʻōhua | The servants, members |

If you do add a plural kaʻi to a collective noun it implies multiple groups. For example:

Nā ʻohana - a group of families

Nā papa - multiple classes (at school)

Nā kaulua - multiple pairs (of shoes, for example)

Nā Kanaka Versus Nā Poʻe

In the case of ke kanaka (a person) and ka poʻe (the collective noun for multiple people) there is another, more subtle, differentiation in concept, as explained in the following diagram: